I wrote this essay to answer for myself the question, “Why is John Wayne my favorite actor?” And in so doing, I hoped to address the common confusion over whether Wayne is an actor at all, along with the questions of what he represents as a political symbol and how that affects our view of his work. The essay was written for American Movie Classics Magazine, the organ of what was once the prime viewing place for classic films on cable television, before AMC started running commercials and switched their emphasis to original programming, allowing Turner Movie Classics to carry the flag instead.

Fittingly, this essay on Wayne is one of the many articles and reviews I wrote during a two-year period to help finance the intensive final stage of work on my 2001 biography Searching for John Ford, a project I had been researching since 1971. I met Wayne briefly at Ford’s rosary vigil after the director died in 1973 and had the chance to watch him work and interview him in 1976, when he was making his last film, The Shootist. But I feel I’ve known him all my life, and I tried to convey that appreciation here while coming to a greater understanding of what he means to me and others.

*****

In 1973, I visited Monument Valley, the eerily beautiful section of the Navajo reservation where John Wayne and John Ford made some of their most celebrated Westerns, such as Stagecoach, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, and The Searchers. There I met a young Navajo who had just returned from service in Vietnam and was still wearing his U.S. Army fatigue jacket. When I asked what he thought about Ford, he replied, “Is he the old guy with the eyepatch? He’s OK.’“

Then I asked what he thought of John Wayne. I assumed this was a touchy subject, particularly since Wayne’s 1971 Playboy interview in which he responded when questioned about the suffering of American Indians, “I don’t feel we did wrong in taking this great country away from them, if that’s what you’re asking. Our so-called stealing of this country from them was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed new land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.”

The young army veteran was so infuriated by Wayne’s comments that he told me if Wayne ever came back to make another movie in Monument Valley, “He’d better watch out, because I’ll be sitting up there in those rocks with my M-1 rifle and I’ll pick him off.”

In the next six years until Wayne died, I often wondered what I would do if I heard that he was going back to Monument Valley to make another movie. Would I alert him to the danger looming in the ancient mesas or simply let history happen?

Wayne has always seemed more than a movie star, a symbolic representation of powerful forces at the center of our national life. In his essay “My Heroes Have Never Been Cowboys,” the Native American writer Sherman Alexie recalled, “Looking up into the night sky, I asked my brother what he thought God looked like and he said, ‘God probably looks like John Wayne.’”

Another young American, Ron Kovic, who came back from Vietnam paralyzed below the waist, ruefully wrote in his memoir Born on the Fourth of July, “I gave my dead dick for John Wayne.” He went to war because he was inspired by Wayne’s Sergeant Stryker in Sands of Iwo Jima. In that 1949 classic, Wayne plays the quintessentially hardboiled U.S. Marine sergeant who gives the young men in his unit ample reason to hate him — until he is shot by a Japanese sniper. Then his men, and the audience, realize they love him. When I first saw the film, I surprised myself by breaking into tears at that moment.

Something about John Wayne has always stirred deep emotions within me, emotions I have never fully understood. He has that effect on most moviegoers, even the ones who, because their politics take precedence over art, are Wayne haters. The archetypal role Wayne plays in our emotional psychodrama explains why he remains the most popular star with the American public today, even though he has been dead for more than two decades.

When someone asked me a couple of years ago why Wayne is my favorite actor, I was at a loss for words. My political views are at an opposite pole to the Duke’s, but that doesn’t affect my view of his work, except to make him an even more intriguing figure. Then I realized that Wayne, as much as George Washington, represents our mythic father figure. Wayne is the larger-than-life father we always thought we wanted but never really had. Not that being a father figure makes Wayne’s screen character unambiguously noble or heroic. He often does upsetting things, as fathers are prone to do in real life. But if you’re in a crisis, military or otherwise, you want Sergeant Stryker to command your unit.

Another misconception about Wayne is that he always played an Indian-hating reactionary in his Westerns. In Fort Apache, a 1948 Ford film that takes the side of the Indians against an arrogant and bigoted U.S. Cavalry officer played by Henry Fonda, Wayne is Captain York, who respects his adversaries. When Fonda’s Colonel Thursday tries to trick the Apache warrior Cochise into returning to the reservation with his people, York responds, “Colonel Thursday, I gave my word to Cochise. No man is gonna make a liar out of me, sir.” Thursday tells him, “There’s no question of honor, sir, between an American officer and Cochise.” York replies, “There is to me, sir. “

Thanks in part to such moments, “It’s impossible not to like the man,” as Dennis Hopper remarked after working with Wayne in The Sons of Katie Elder. But patriarchy, heroism, patriotism, and all the other qualities Wayne represents have come under severe questioning in recent years. His “My country, right or wrong” attitude seemed archaic even by 1960, when he donned a coonskin cap to play Davy Crockett in his own production of The Alamo. That lumbering, corny, but heartfelt epic holds up surprisingly well today as a stirring piece of personal filmmaking.

Being unabashedly archaic was always a large part of Wayne’s appeal. His brand of rugged individualism belongs to the nineteenth century, when American revolutionary ideals were put to the test in internecine warfare. For better or worse, Wayne deserves the title writer-director John Milius bestowed on him in 1975, “The Last American.”

Wayne did not achieve such stature simply by standing around in statuesque poses and “playing himself,” as his detractors assume. He explained that an actor can’t just play himself onscreen, but needs to create a character to inhabit. Wayne has never been given enough credit for the conscious artistry that went into that creation, or for the sense he showed in listening to demanding, first-rate directors such as Ford, Howard Hawks, and Raoul Walsh. From them he learned the qualities of relaxation and silent eloquence of facial expression and body language that suited him so well over the years.

When I interviewed Wayne on the set of his last film, The Shootist (1976), he told me that he developed his characteristic line delivery of hesitating in mid-sentence because it compels the audience to keep their eyes on him, such as when he says half-jokingly in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “Liberty Valance is the toughest man south of the Picketwire . . . next to me.” Wayne’s hesitation conveys a sense of vulnerability that humanizes his characters in much the same way Ernest Hemingway makes us feel the secret fragility of his outwardly macho protagonists.

Wayne won his Oscar for his genial self-parody in True Grit (1969) as the drunken, one-eyed Marshal Rooster Cogburn. But his brilliance should have been honored long before for such masterful performances as Sergeant Stryker, Tom Dunson in Red River, Nathan Brittles in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Sean Thornton in The Quiet Man, Ethan Edwards in The Searchers, John T. Chance in Rio Bravo, and Tom Doniphon in Liberty Valance. The protean actors who put on beards and heavy makeup and play a wide range of eccentric characters get most of the glory. But the level of authenticity John Wayne reaches onscreen is far more difficult to achieve.

#####

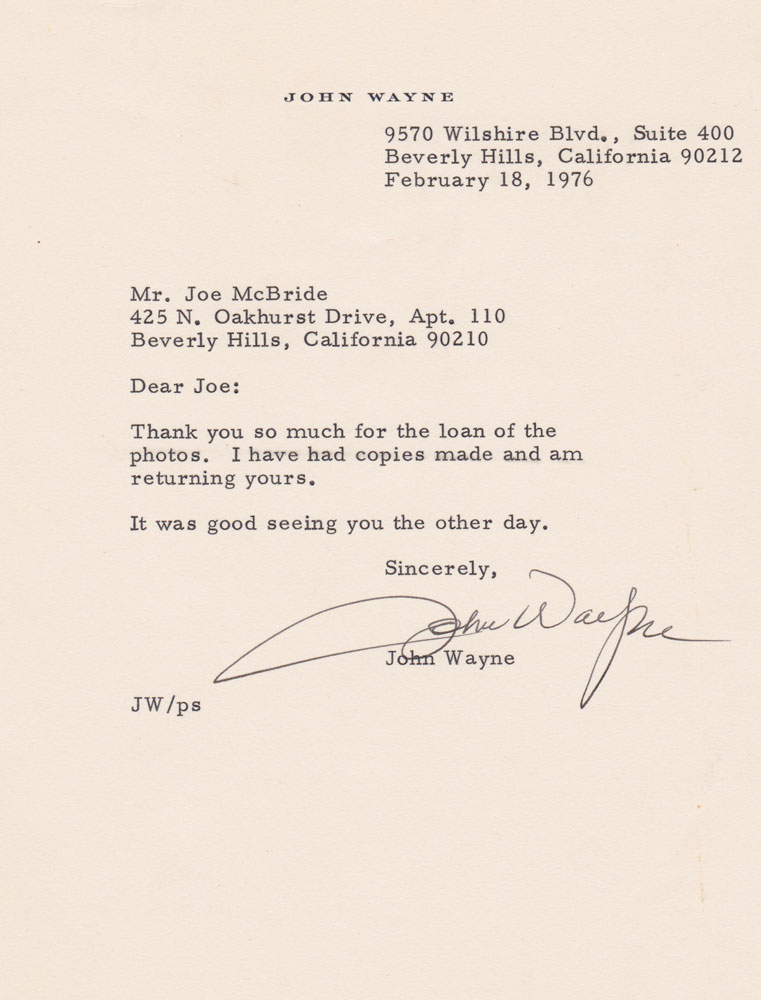

John Wayne letter to the author about their interview

on the set of THE SHOOTIST (1976).